How to run a successful BRI chapter, by Mary Kathryn Hahn

June 4, 2016 by cmonte

[fve]https://youtu.be/EqFW5RC5VIk[/fve]

Mary Hahn, from SUNY Downstate Medical School, experienced a bumpy ride establishing a BRI chapter at her school. In spite of a few setbacks — not the least of which was the campus environment not entirely welcoming of free market ideas — Mary persevered, and not only established a successful BRI chapter, she also provided a place for other like-minded medical students to be able to participate in a conversation for free market healthcare.

Swaying Hearts and Minds to Healthcare Freedom — Part III (of 3): Cash based healthcare system

May 27, 2016 by

The Blog post was written by a BRI Student Leader who wishes to remain anonymous.

… And now for some basic questions about a cash based healthcare system, since we’ve put the philanthropic and economic questions to rest…

I’ve heard some conservatives advocating for more cash-based medical care. The insurance plan I have now is expensive, but it covers most of my healthcare needs.

To understand the state of healthcare in America today, it is useful to understand the historical background in which our system developed. Our tradition of employer-sponsored health insurance arose during the 1940s in response to a government-imposed freeze on salaries. In order to supplement employees’ income, companies began offering health insurance benefits. When the wage freezes were repealed, employer-sponsored insurance did not go away with them. Americans became accustomed to employer-sponsored insurance, and being covered by a comprehensive health insurance plan became the norm. Unfortunately, this has led us into a state of over-insurance: Americans are paying excessive amounts of money for healthcare benefits that they previously purchased directly through cash payments.

Insurance is a tool to hedge against unexpected misfortunes, like your house burning down or a natural disaster. It is not meant to be used for routine expenses like paying your electric bill or buying groceries. However, Americans now buy health insurance that includes a spectrum of both routine and catastrophic medical care. When proponents of free enterprise talk about cash-based systems, they are advocating that we shift back to a system in which consumers pay for routine medical costs out of their own pocket. The point of this is to align consumers’ incentives so they are naturally drawn to make the most efficient economic decisions. If you are responsible for paying for your routine healthcare, you will be inclined to search for the services that fit your preferences, and you will be hesitant to consume services that are unnecessary. It is easy to spend someone else’s money, but people spend much more deliberately when it is their money in question. The only “single-payer” for routine care should be individual patients themselves.

What are the benefits of moving to a cash based healthcare system?

If we shift back to a cash-based system for routine medical expenses, health insurance still has an essential role to play. Health insurance will still be essential to insure against unexpected, catastrophic medical events. The price of this insurance should be reasonable because it would only cover medical events over a certain dollar amount; all of the routine care that is inflating health plan pricing today would be excluded from catastrophic insurance.

A system based on mixed cash payments and catastrophic insurance would be extremely beneficial for patients and their doctors. Cash payments for routine care would vastly simplify the insurance payments fiasco that doctors experience today, reduce administrative costs, and allow physicians to spend less time filling out paperwork and more time with their patients. Physicians and patients around the country are beginning to embrace this system, and early results show that the cost of care is decreasing, health outcomes are stronger, and physician satisfaction with their work is much higher. A few examples of successful cash based practices include the Surgical Center of Oklahoma, Atlas MD, and Gold Direct Care.

Although this concludes our series on free market medicine point/counterpoint, I hope it is just the beginning of the dialogue on how we can work together to transform American healthcare. Do not hesitate to share your beliefs with your peers, despite what they might believe currently. Dynamic social change occurs because small groups of people are willing to speak for what they believe, even if it is unpopular.

This is our time.

May 25, 2016 by

The Blog post was written by a BRI Student Leader who wishes to remain anonymous.

These questions naturally follow the first (mistaken, in my view) assumptions in Part I of this series—first, that we have a completely, or mostly, free market healthcare system, and second, that doctors should be more altruistic perhaps than other service providers.

I believe all people deserve access to high quality healthcare services regardless of their ability to pay. What will happen to the poor and disadvantaged in a free market system?

A system that encourages transparency, empowers individuals to make efficient economic decisions, and removes class barriers, offers the poor the best opportunity to receive high quality healthcare. Considering the needs of the poor is essential when advocating for healthcare reform. The social paradigm that The Right loves markets and hates the poor is not only political invective, but completely false. Conservatives and libertarians appreciate free enterprise as the single most important factor in lifting billions of people out of poverty in the last century. Free enterprise is the greatest driver of wealth creation in the history of mankind. Admittedly, The Right often comes across as out-of-touch with the needs of the poor because our dialogue focuses too much on policy and too little on compassion.

Despite conservatives’ ineffective narrative, I submit that free enterprise offers the poor their best chance to receive high quality healthcare. However much we hope to improve healthcare, there will always be individuals who cannot afford to pay for their own care. Medicaid—government healthcare for the poor—still has a role to play in providing the means to care for these people. Today, Medicaid patients are often viewed as less desirable by physicians and hospitals because Medicaid reimbursement rates are substantially lower than private insurance, not to mention the paperwork and bureaucracy involved. This produces two possible outcomes, both of which are bad for the poor: 1) a selection bias that makes it difficult for them to find a physician, and 2) a care bias that sometimes leads them to receive inferior care compared to a privately insured patient. Both of these outcomes are unacceptable but expected results of the system that we have right now. Medicaid itself has led to the formation of a de facto caste system in terms of access to care and payments.

“Despite conservatives’ ineffective narrative, I submit that free enterprise offers the poor their best chance to receive high quality healthcare.”

Feasible solutions exist to simultaneously address the healthcare needs of the poor and eliminate the stigma attached to Medicaid. Instead of funneling money to the states to finance Medicaid as its own insurance plan, the Federal government could use these funds to finance health savings accounts (HSA) for eligible Medicaid beneficiaries. Individuals who pass an income acid test, for example 125% of the federal poverty line, would be eligible to receive an annual deposit of funds into a tax-free bank account (an HSA). Funds deposited into the HSA can only be used for healthcare expenses. The HSA beneficiary decides how he wants to spend the money—on primary care services, catastrophic insurance premiums, elective care, etc. Following the logic of my prior argument for more cash-based primary care, Medicaid beneficiaries could use their HSAs to pay cash for planned expenses and to pay the premiums on a catastrophic insurance plan.

This solution—tax-free savings accounts to pay cash for routine care and premiums on a catastrophic plan—is not just what I wish for the poor, but what I wish all members of society would have the opportunity to purchase. Today, due to Medicaid’s low reimbursement rates, many physicians intentionally limit the number of Medicaid patients they accept into their practice. With this solution, it would no longer matter to healthcare providers whether their patients are Medicaid (or Medicare) beneficiaries because all patients would purchase the same basic services and be covered by a private catastrophic plan. This solution empowers individuals to make decisions for themselves without intermediary meddling and removes the government from its unnecessary and inappropriate role as the poor’s medical care overseer.

Doctors should be committed to their patients first and worry about how much they’re being paid later. How do you reconcile your interest in policy and finance with the attention you should be taking in your patients?

Physicians commit themselves to nearly a decade (or more) of intense medical education—after obtaining their undergraduate degrees. These years of rigorous education give way to even more intense years of clinical practice. Unfortunately, many middle aged and older physicians are discovering that the burden of triple-documenting their clinical encounters, haggling with insurers for payment, and managing the regulatory environment is inhibiting the main reason they became a physician in the first place: to take care of their patients.

My interest in healthcare policy stems not from a concern with how much I will be paid once I become a physician, but concern for my freedom to determine the scope and direction of my practice. I am, of course, concerned with payments, but I am more frightened by the increasing dissatisfaction of physicians for the noble profession that so many men and women enter with the intent to become healers of the sick, not slaves to the Electronic Medical Records (EMR). I am one of thousands of first-year medical students across the country excited to begin our long medical careers; but, the statistics say in just a few years, a large number of my colleagues will be dissatisfied with their compensation, irritated with their workload, and concerned about the limited time they are allowed to spend with patients.

The market solutions I advocate for are not magic bullets, but they are progress towards fostering an environment that encourages efficient spending, rewards high quality delivery, and allows physicians to build the relationships for which most of us entered into the practice of medicine in the first place. Top-down regulation has consistently burdened the medical profession and driven up the cost of care across the board. If physicians do not begin speaking up for their interests, they will continue to see their autonomy wrested away by out-of-touch interests. Long term effects of physician silence will be bad for physicians and worse for their patients.

Let us seek to enable a healthcare ecosystem that empowers both buyers and producers of care to enter into mutually beneficial voluntary exchange without the interference of intermediaries with no vital interest in our relationships.

In Part III, we examine some fundamental questions about insurance, regardless of which political side of the fence you prefer on this issue.

May 23, 2016 by

The Blog post was written by a BRI Student Leader who wishes to remain anonymous.

Just a few weeks ago, I departed Benjamin Rush Institute’s 4th Annual Leadership Conference emboldened in my beliefs that a strong free enterprise system—including political equality, the rule of law, transparency, and limited regulation—offers American healthcare its best chance to rein in costs, foster innovation, and serve the needs of the poor.

Throughout the conference, students, physicians, and policy leaders discussed not only the solutions to healthcare problems, but how we will go about beginning difficult conversations with those who disagree. Dr. Arthur C. Brooks, PhD, eminent conservative scholar and American Enterprise Institute president, spoke directly to this notion when he introduced the subject of political motive asymmetry. That is, many people in the United States today believe that their beliefs and intentions are virtuous while those of the opposition are rooted in selfishness and maleficence. “Conservatives hate the poor,” cry liberals. “Liberals are ruining America,” the Right screams back — hence, our current state of gridlock and malcontent with Washington D.C.

To make strides on the many issues we face, the political spectrum must be willing to enter into respectful, good faith discourse on the issues. In the words of Brooks, we must not be uniform in our beliefs, but we must be unified in our respect for each other.

Therefore, I relished the opportunity when it presented itself recently, to begin a dialogue with several of my liberal friends on the effects of free enterprise in healthcare. Although I may not have flipped their opinions, I hope I planted ideas in their minds that will inspire them to think critically about the path forward. The debate was productive because it began with recognition of our common ground: a desire to restore sanity to a system that has become untenable to navigate and pay for.

Although it is feasible to obtain competent knowledge of policy through diligent study, facilitating transformative discourse takes delicate skill and much practice. The healthcare solutions we desire to implement will not occur unless we begin changing the hearts and minds of those who oppose us. I implore you to begin planting free market idea seeds now, so one day soon people across this great nation will reap the rewards.

Because I have taken on having conversations with many people as a way to advance understanding free enterprise in healthcare, over the next few weeks I will share the main questions and arguments I have encountered. I hope that others will find them interesting and empowering so that more of us can also promote these vital ideas . . . all while never forgetting to start from a basis of mutual respect, while not losing one’s vision or principles.

I’ll start with the most pervasive and overarching myth and misconception, namely that…

We already have a system that is close to being a free market, and it’s produced the catastrophe we are in today. What makes you think more free enterprise reforms will improve American healthcare?

As it stands today, the US healthcare system is far from a “free” market. Over the last half-century, the market has faced unprecedented new regulatory and administrative burdens in addition to the entrance of the government as the largest “payer” for healthcare. In parallel with the establishment of government health programs (Medicare and Medicaid), our system has become infuriatingly convoluted. Government, both state and federal, impose undue regulatory burdens on doctors and insurers that unanimously confuse all parties while placing unnecessary burdens on the delivery of care. The cost of these regulatory and administrative burdens is ultimately passed on to privately insured individuals and US taxpayers—who are often the same people.

A fundamental characteristic of free enterprise is the individual’s ability to engage in mutually beneficial, voluntary exchange. Unfortunately, American healthcare has evolved in a manner that distorts individuals’ decision-making ability, especially when it comes to price and quality. Patients find it nearly impossible to make informed decisions for themselves because prices are either hidden from view or distorted by a mass of tangled insurance benefits. Our healthcare providers are forced to accept intense administrative oversight and to collectively spend billions of dollars on administrative staff in order to receive payments for their services from insurers. Physicians are increasingly forced to practice within a confined environment with reduced autonomy to make the right decisions for their patients. Instead of being completely attentive to what is right for their individual patients, providers are influenced by what the government and private insurance will reimburse them for.

If we had a true free enterprise system in healthcare, every person would have the ability to make informed medical decisions without the disruption of intermediaries. Empowering both producers and consumers of care to participate in mutually beneficial, voluntary exchange without coercion is key to improving the American healthcare system.

I hope this has given you some food for thought and more than talking points supporting free enterprise in healthcare — substantial facts and evidence to bring to any respectful discussion, whether you seek to inform those against free market healthcare, or if you are currently one who opposes free market healthcare. Please stay tuned for Part II: What about the Poor? And, How should doctors be paid?

Ohio State debate: Government Healthcare vs Free Market

May 18, 2016 by cmonte

[fve]https://youtu.be/g9V9nb3X5-g[/fve]

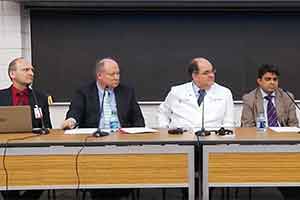

Debate: Government Healthcare vs Free Market

5/2/2016 at Ohio State University College of Medicine

Be it RESOLVED: The Federal Government Can Provide More Compassionate and Efficient Healthcare for All Americans than the Free Market.

Do you think you know enough about government-run healthcare? Free market healthcare? Ohio State University College of Medicine BRI chapter and Students for a National Health Program (SNaHP) held a debate wherein free markets were pitched head on against federal government, single payer healthcare programs. Which system provides the best solutions for the most people at the best prices? Which takes better care of the doctor-patient relationship? Which is more efficient?

In spite of ACA’s passage in 2009, the debate over the general direction of much needed health reforms continues, with some arguing that the law takes us in the wrong direction and others arguing that the law has not given the government enough control. Three debaters will uphold the resolution, and two debaters will argue in opposition.

ARGUING THE AFFIRMATIVE:

BRI debate Dr. Bradford W. Cotton is a full-time emergency physician in the Columbus metro area. Dr. Cotton began his career in EMS as a volunteer EMT/Firefighter and emergency department tech in 1978, graduating from Kent State University School of Nursing 1982. EMS career included 3 years with the City of Cleveland EMS. Dr. Cotton graduated Ohio State University College of Medicine 1991 and OSU emergency medicine residency 1994 earning several clinical honors. Dr. Cotton has served 39 years now in EMS / emergency medicine, including 10 years as EMS Medical Director for Ross County, Ohio and on Region V EMS Advisory Board. Dr. Cotton published research on EMS transmission of 12 lead EKGs leading to updating of Ohio EMS Board rules.

Dr. Donald Mack From his bio: As a family physician for 30 years, I have done birth to death family medicine in a rural setting, and continue to see the full range of ages in my office practice. Additionally, I am focusing clinical time on geriatric long term care and end of life care. My goal is to increase interest and knowledge among medical students, family medicine residents, and fellows in the areas of Geriatrics and Hospice and Palliative Medicine, with the ultimate goal of improving the care of vulnerable, elderly patients. I want to make sure that we have highly skilled physicians to take care of our aging world, my family, and eventually, me.

ARGUING IN OPPOSITION:

Dr. Beth Haynes, Executive Director, Benjamin Rush Institute Previously in private practice with board certification in both Family Practice and Emergency Medicine, Dr. Haynes has been working full time in healthcare policy for the past seven years. She obtained her MD from the University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine and her residency training at University of Wisconsin in Madison. She also volunteers as an executive board member of Docs 4 Patient Care Foundation, United Physicians and Surgeons of America and the Dr. Joseph Warren Institute.

Dr. Saurabh (Harry) Jha, Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania Dr. Jha is a radiologist and can be reached on Twitter @RogueRad. His articles have appeared in Kevin.MD and elsewhere.

Moderator: Dr. Ryan Nash, MD, MA is the Director of The Ohio State University Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities.He is an Associate Professor of Medicine and holds the Hagop Mekhjian, MD, Chair in Medical Ethics and Professionalism at the College of Medicine. Dr. Nash is a Clinical Bioethics consultant and Healthcare Ethics Advisor for the OSU Medical Center and is the editor of the Ohio State University Press book series on Bioethics and Medical Humanities. He has published one book, three book chapters, and several essays related to bioethics and has presented numerous scientific papers. Dr. Nash currently serves on the Ethics Committee for the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Strengthening Medicaid to protect protect the most vulnerable, by Joshua Trent

May 7, 2016 by cmonte

[fve]https://youtu.be/ZE2kJOIb6ac[/fve]

During BRI’s Leadership Conference Policy Day hosted at AEI, we were honored to have Joshua B. (“Josh”) Trent from the Committee on Energy and Commerce, US House of Representatives. Mr. Trent spoke on the benefits of free market principles used even to render medicaid — a government program — healthier, so as to produce better outcomes for all.